Engineering The Blackest Black: Riflebird Shows The Way

Black usually sounds simple, until you try to make the

blackest black.

Scientists call it ultrablack: a colour that reflects less than 0.5% of

incoming light. It is prized for cameras, telescopes, and solar panels—and

notoriously hard to make. Worse, many ultrablack materials lose their darkness

when viewed from an angle.

Now, a team at Cornell University has cracked the problem -

with help from a bird.

Inspired by the magnificent riflebird, whose feathers appear

impossibly black, researchers at Cornell’s Responsive Apparel Design (RAD) Lab

have created the darkest fabric ever reported. And unlike previous ultrablack

materials, this one is wearable, scalable, angle-independent—and made from

wool.

Nature, it turns out, has been doing ultrablack better than

humans for millennia.

The riflebird’s feathers don’t rely on pigment alone. Their

secret lies in microscopic structures - tightly packed barbules that trap light

and force it to bounce inward until almost none escapes. The Cornell team

decided to copy that trick.

Their process is surprisingly simple and elegant. First,

they dyed white merino wool using polydopamine, a synthetic version of melanin,

the same pigment found in birds, fish, and butterflies. Then they placed the

fabric in a plasma chamber, where controlled etching created nanofibrils - tiny

spiky structures that mimic the riflebird’s feather architecture.

The result? Light enters the fabric and gets lost.

Instead of reflecting outward, light ricochets between the

nanofibrils until it is almost entirely absorbed. “That’s what creates the

ultrablack effect,” explains doctoral researcher Hansadi Jayamaha.

The numbers are striking. The fabric achieved an average

reflectance of just 0.13%, making it the darkest textile ever reported. Even

more impressive, it stays ultrablack across a 120-degree viewing range,

remaining visually unchanged from sharp angles where other materials turn shiny

or grey.

For designers, this changes everything.

“Most ultrablack materials aren’t wearable,” says Larissa

Shepherd, assistant professor and director of the RAD Lab. “Ours is. And it

stays ultrablack even from wider angles.” The research, published on November

26 in Nature Communications, positions ultrablack not just as a lab curiosity,

but as a functional textile.

The implications go far beyond fashion. According to

researcher Kyuin Park, the fabric could be used in solar thermal applications,

helping absorb and convert light into heat. Potential uses include

thermo-regulating camouflage, advanced protective gear, and performance

apparel.

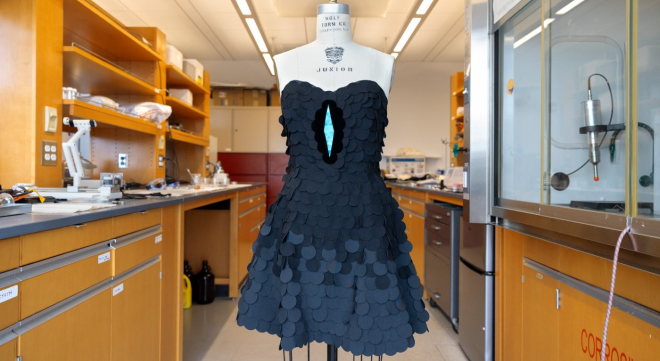

Still, fashion provided the ultimate proof. A dress designed

by Zoe Alvarez ’25, inspired by the riflebird, used the ultrablack fabric

alongside iridescent blue. When image contrast and brightness were altered,

every colour shifted - except the ultrablack. It stayed black. Perfectly.

Cornell has filed for provisional patent protection and is

exploring commercialisation through its Ignite Innovation Acceleration program.

From feathers to fibres, ultrablack has finally found a

fabric-friendly future and it might just redefine what “black” really means.

“Most ultrablack materials aren’t wearable,” says Larissa Shepherd, assistant professor and director of the RAD Lab. “Ours is. And it stays ultrablack even from wider angles.” The research, published on November 26 in Nature Communications, positions ultrablack not just as a lab curiosity, but as a functional textile. The implications go far beyond fashion. According to researcher Kyuin Park, the fabric could be used in solar thermal applications, helping absorb and convert light into heat. Potential uses include thermo-regulating camouflage, advanced protective gear, and performance apparel.

If you wish to Subscribe to Textile Excellence Print Edition, kindly fill in the below form and we shall get back to you with details.