Water Will Decide Who Produces And Who Shuts Down

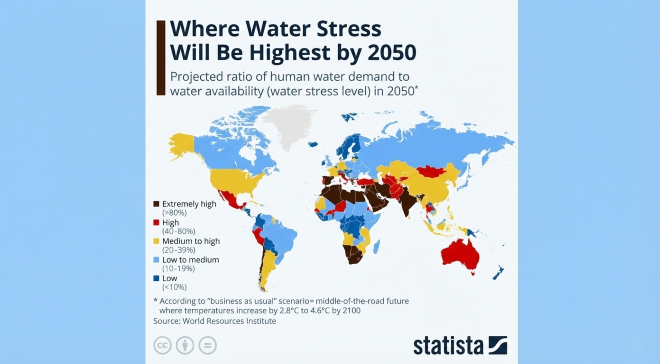

Water

scarcity will emerge as a geopolitical and economic constraint, not just a

climate issue, by 2026, according to Ernst & Young’s 2026 Geostrategic

Outlook. After decades of carbon-focused climate policy, water is now becoming

a decisive factor shaping industrial strategy, supply chains and global power

equations.

The

stress is already real. Nearly four billion people experience severe water

shortages for at least one month every year. Heatwaves and droughts in 2024–25

showed how quickly water shortages translate into higher food prices,

inflationary pressure and political unrest. Climate change is accelerating the

problem by disrupting rainfall patterns, increasing evaporation, and

intensifying floods and droughts, even as demand rises across agriculture,

cities and industry.

When

digital ambition hits physical limits

What

makes the coming phase more disruptive is water’s collision with the global

race for digital and industrial dominance. Semiconductor manufacturing, AI

infrastructure, mining of critical minerals and hyperscale data centres all

require vast, reliable volumes of freshwater, often in regions already under

stress.

Advanced

semiconductor fabrication is among the most water-intensive manufacturing

processes in the world. Research published in 2025 shows that a single

leading-edge fab processing around 40,000 wafers a month can consume up to 4.8

million gallons of water per day, even after recycling, comparable to a small

town’s daily use.

Data

centres running AI workloads pose a parallel challenge. Facilities using

evaporative cooling can require millions of gallons of water daily, triggering

local resistance in water-stressed regions. While waterless cooling systems are

emerging, they often raise energy consumption and capital costs, creating a

three-way trade-off between water, energy and infrastructure.

Industries

under strain - beyond farms and power

While

agriculture and energy remain central to water politics, pressure is spreading

across manufacturing sectors.

Textiles

and apparel: Water-intensive textile clusters in South

Asia face growing scrutiny over freshwater extraction and pollution, creating

supply chain and reputational risks for global brands.

Food

and beverages: Water is both an input and a product,

making operations vulnerable in stressed basins.

Mining: In

Chile’s Atacama region, lithium expansion has intensified disputes over indigenous

water rights, despite moves toward desalination.

Urban

development: Assured water supply is increasingly

shaping where cities can expand, and where they cannot.

Arizona

shows how water caps growth

The

arid south-western US offers a stark example of water becoming the binding

constraint. In Arizona, prolonged drought collided with rapid semiconductor

expansion, forcing water regulation to the centre of industrial policy.

In

2025, the state tightened groundwater rules and began allowing agricultural

water savings to be converted into urban and industrial credits. The contrast

is telling: Arizona’s first such approval freed enough water for 825 homes

annually, while a single advanced chip fab can consume four times that volume

every year. For industry, water access, not capital or technology, is now the

decisive factor.

Water

as a geopolitical instrument

Water

is also becoming a tool of statecraft. The 2025 suspension of the Indus Waters

Treaty during India–Pakistan tensions highlighted how shared rivers can be

weaponised. Disputes persist over the Nile, Mekong and Brahmaputra, while

cyberattacks on water utilities are rising, elevating water infrastructure to a

strategic security asset.

What

this means for business

EY

warns that water risk must move into core strategic planning. Scarcity can halt

production, disrupt supply chains and erode social licence to operate.

Governments and companies alike are being pushed toward water-efficient

technologies, recycling, tighter regulation and long-term infrastructure

investment, not as sustainability choices, but as prerequisites for economic

resilience.

Heatwaves and droughts in 2024–25 showed how quickly water shortages translate into higher food prices, inflationary pressure and political unrest. Climate change is accelerating the problem by disrupting rainfall patterns, increasing evaporation, and intensifying floods and droughts, even as demand rises across agriculture, cities and industry.

If you wish to Subscribe to Textile Excellence Print Edition, kindly fill in the below form and we shall get back to you with details.