Mass Protests Sweep Europe Over EU-Mercosur Trade Deal As Farmers Fear Economic Fallout

Thousands of farmers across the European Union took to the

streets this weekend in one of the largest agricultural protests seen in years,

voicing fierce opposition to the EU’s newly approved free-trade agreement with

the Mercosur block of South American nations. Farmers in Ireland and France

mobilised tractor convoys, blockades and rallies to spotlight concerns that the

accord will expose domestic agriculture to unfair competition and undercut

local livelihoods.

In Athlone, central Ireland, tens of thousands of farmers

and supporters gathered on January 10, driving tractors along major roads and

rallying at Technological University of the Shannon under banners reading “Stop

EU-Mercosur” and slogans accusing EU leaders of abandoning agriculture.

Ireland’s Government had voted against the deal, saying it lacked sufficient

safeguards to protect stringent food safety and environmental standards.

Protesters fear the pact could open local markets to an additional 99,000 tonnes

of lower-cost beef from Mercosur nations such as Brazil and Argentina,

threatening the competitiveness of Irish beef and dairy producers in a sector

that remains a major employer in rural regions.

Simultaneous demonstrations occurred in France, where

farmers drove tractors into central Paris, blockading routes near the Eiffel

Tower and Arc de Triomphe to pressure national and EU leaders. French President

Emmanuel Macron has indicated that France will oppose the deal, echoing similar

concerns about cheap imports and inconsistent regulatory standards.

Opposition to the trade pact is not limited to Ireland and

France. Farmers in Poland, Belgium and Hungary have also staged protests,

warning that Mercosur imports could disrupt long-standing agricultural

practices and weaken food security. Critics argue that the pact, which would

create one of the world’s largest free-trade areas encompassing markets of

nearly 800 million people, prioritises industrial exports such as machinery,

chemicals and pharmaceuticals at the perceived expense of farming communities.

EU policymakers argue the agreement offers significant

economic gains, including expanded export opportunities for European

manufactured goods and reciprocal market access. Yet, the farming bloc remains

deeply divided, and the trade deal still requires approval by the European

Parliament before it can take effect. Lobby groups such as the Irish Farmers’

Association have vowed to intensify efforts to build opposition in the

legislature and push for stronger protections or renegotiation of contentious

provisions.

The unfolding protests mark a significant flash point in

European trade politics, underscoring the complex balancing act between

liberalised commerce and the protection of strategic domestic industries. With

parliamentary ratification pending, the outcome of the Mercosur deal will test

the EU’s capacity to reconcile global trade ambitions with farmer livelihoods

and food standards that many Europeans hold dear.

Opposition to the trade pact is not limited to Ireland and France. Farmers in Poland, Belgium and Hungary have also staged protests, warning that Mercosur imports could disrupt long-standing agricultural practices and weaken food security. Critics argue that the pact, which would create one of the world’s largest free-trade areas encompassing markets of nearly 800 million people, prioritises industrial exports such as machinery, chemicals and pharmaceuticals at the perceived expense of farming communities.

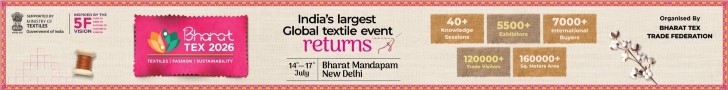

If you wish to Subscribe to Textile Excellence Print Edition, kindly fill in the below form and we shall get back to you with details.