The Zero-Duty Illusion: US Trade Pact Limits Bangladesh's Gains

Bangladesh’s newly signed reciprocal tariff arrangement with

the United States has triggered intense debate across South Asia’s textile

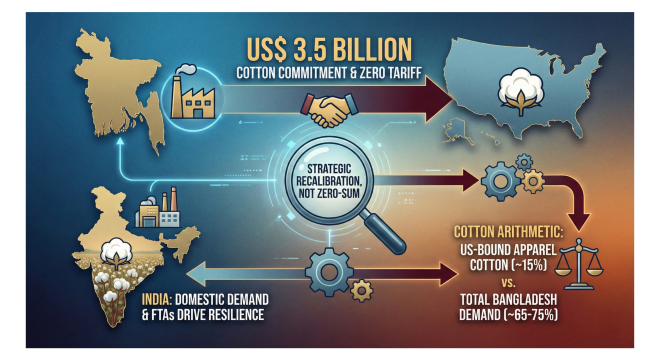

ecosystem. At the centre of the discussion is a reported US$ 3.5 billion cotton

purchase commitment and zero reciprocal tariff access for garments made from

US-origin cotton and man-made fibres.

But does the cotton arithmetic justify the scale of the

commitment? And does this shift pose a threat to India’s cotton and textile

sector?

A closer look at the numbers provides clarity.

How much cotton is actually used for US apparel exports?

In 2024, Bangladesh exported approximately US$ 7.2 billion

worth of apparel to the United States, about 18–19% of its total garment

exports. Assuming that 80% of those exports are cotton-based garments, the

cotton apparel value equals US$ 5.76 billion

In typical FOB garment costing structures, raw cotton fibre

accounts for roughly 10–12% of export value, depending on product mix (basic

knits vs denim-heavy categories).

Using this range:

- At 10% fibre cost share → US$576 million worth of raw cotton

- At 12% fibre cost share → US$691 million worth of raw cotton

Assuming an average US cotton export price of approximately

US$ 2.50 per kg, this translates into 230,000 to 275,000 metric tonnes of

cotton annually.

Even using a higher 15% fibre share assumption, cotton usage

would reach only around 345,000 tonnes.

Now compare this with Bangladesh’s total annual cotton

consumption.

Bangladesh’s cotton requirement

Bangladesh consumes approximately 85 lakh bales (8.5 million

bales) per year - equivalent to roughly 1.7 to 1.9 million metric tonnes.

Nearly all of this is imported, as domestic production is negligible.

Historically, sourcing has been diversified across:

- Brazil

- India

- West African origins

- United States (in varying shares)

The key takeaway:

Cotton used for US-bound apparel likely represents around

15% of Bangladesh’s total cotton consumption.

The US$ 3.5 billion cotton commitment: A scale mismatch

If US$3.5 billion worth of cotton were purchased at roughly

US$2.50/kg, the volume would equal 1.2 to 1.4 million metric tonnes. That is

nearly 65–75% of Bangladesh’s annual cotton requirement.

This clearly exceeds the cotton required solely for US-bound

garments.

Therefore, one of three realities must apply:

- The US$ 3.5 billion purchase is spread across multiple years;

- Bangladesh will incorporate US cotton into garments exported

to other markets;

- Mills will significantly rebalance fibre blending strategies.

Operationally, Bangladesh cannot rely on a single origin due

to staple length variations, blend optimisation needs, freight economics, and

price arbitrage cycles. Diversification remains structurally necessary.

The agreement therefore appears less about servicing

US-bound garments alone and more about deepening upstream supply-chain

alignment with the United States.

What does this mean for India?

Concerns have surfaced that Bangladesh’s tilt toward US

cotton may displace Indian exports. However, supply-side realities suggest

otherwise.

Bangladesh imports about 85 lakh bales annually, and India

currently exports roughly 12 lakh bales to Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, India produces around 370 lakh bales per year.

However, strong domestic spinning demand, export commitments across yarn and

fabrics, and textile value chain expansion require India to import nearly 50

lakh bales annually.

This is a crucial structural fact: India is not surplus in

cotton.

Domestic consumption remains strong enough that India often

supplements supply through imports to stabilise quality and availability.

Are Indian cotton farmers at risk?

The evidence suggests limited downside risk.

India’s textile ecosystem is entering an expansionary phase,

supported by:

- A concluded FTA with the United Kingdom and the European

Union

- Ongoing discussions toward a broader India–US trade framework

- Various other trade deals

These developments are expected to stimulate spinning,

weaving, processing, and garmenting capacity, driving higher domestic cotton consumption.

Given limited scope for rapid acreage expansion or

productivity breakthroughs, India may actually increase cotton imports over

time.

In this context, fears of structural demand collapse for

Indian cotton appear overstated.

Zero-duty access: Not Bangladesh -exclusive

Another overlooked point is that zero-duty access linked to

US-origin fibre is not necessarily unique to Bangladesh.

Under reciprocal tariff frameworks introduced during the

administration of Donald Trump, countries incorporating a minimum threshold of

US-origin raw materials in finished goods may qualify for preferential access,

subject to negotiated terms.

Indian textile bodies have raised similar mechanisms in

bilateral discussions. Given India’s integrated value chain and scale

advantages, any structural edge granted to Bangladesh may not remain

unilateral.

Strategic conclusion

The Bangladesh-US arrangement undoubtedly incentivises

increased US cotton usage. However, the arithmetic reveals that cotton required

for US-bound apparel is only a fraction of Bangladesh’s total fibre demand.

For Bangladesh, the deal represents a strategic sourcing

recalibration rather than total dependence.

For India, the evolving trade landscape appears more

opportunity than threat. Domestic demand strength, ongoing FTAs, and value

chain expansion suggest resilience in cotton consumption dynamics.

This is not a zero-sum cotton contest. It is a broader

realignment of textile supply chains in a geopolitically sensitive trade

environment where scale, diversification, and policy agility will determine

long-term advantage.

The Bangladesh-US arrangement undoubtedly incentivises increased US cotton usage. However, the arithmetic reveals that cotton required for US-bound apparel is only a fraction of Bangladesh’s total fibre demand. For Bangladesh, the deal represents a strategic sourcing recalibration rather than total dependence. For India, the evolving trade landscape appears more opportunity than threat. Domestic demand strength, ongoing FTAs, and value chain expansion suggest resilience in cotton consumption dynamics.

If you wish to Subscribe to Textile Excellence Print Edition, kindly fill in the below form and we shall get back to you with details.